I thought to create a theatre piece that could exist without the boundaries that separate performance and installation art. Working under the banner of the title TIME, I purposefully challenged myself to deny the notion of time itself —— Ryuichi Sakamoto

Sakamoto's reflections on time can be traced back to the early 1980s. However, it was during the creation of his 2017 album async—after recovering from cancer—that the Japanese composer began contemplating the theater piece TIME. He sought to explore music that defied traditional temporal structures, creating compositions without a clear beginning or end. TIME continued Sakamoto's investigations into time, boldly negating conventional notions of time the concept and using dreams to illustrate the multiplicity of time.

In this interview, stage director Shiro Takatani discusses his final collaboration with the musical maestro and their endless exploration of time.

Interview reprinted from the TIME Japan tour booklet, edited by FestMag

The "uncertainty of time" plays a pivotal role in this work.

People tend to envision time as unfolding on an orderly straight line with tidy correlations between cause and effect. When we think of time, we think of a clock, whose hands measure the regimented movements of the sun and moon.

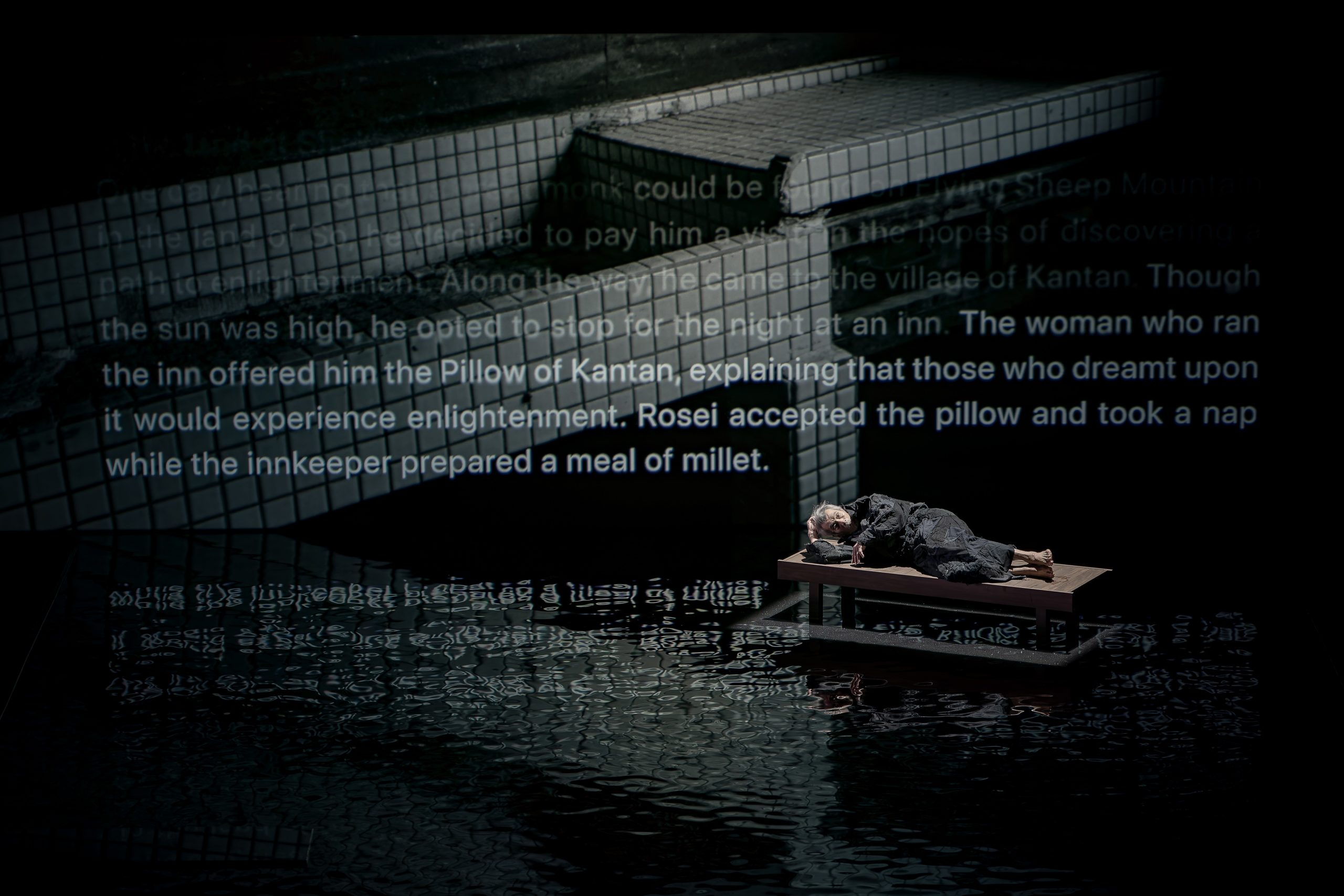

During the performance of TIME, a path is created through the water on stage using brick-like blocks. This idea of using small building blocks to create something larger represents the origin of mathematics. Things become easier to understand when broken down and organised into small, manageable pieces. Many people today find comfort and stability in this way of living. But what if there were another, freer outlook on time? Perhaps the world would become more hospitable to a wider range of people with diverse sensibilities.

How hands-on were you in directing dancer Min Tanaka and shō player Mayumi Miyata heading into the first rehearsal?

Tanaka, Miyata and Ryuichi Sakamoto are all outstanding artists. We all shared the same fundamental understanding of the piece. The only material provided at rehearsal was a bare-bones script. Everyone fully committed and filled out the performance with their own emotional touch. It was exciting to watch. I felt something new that I could not have anticipated from the script alone. The same is true for Noh theatre. No matter how many times you see a piece, you still discover something new.

As Sakamoto said: "The goal is not to repeat the same performance over and over, but rather, to explore what arises on the spur of the moment."

Yes. Unfortunately, he could not join us for the rehearsals in Amsterdam. But we sent him videos each day and he responded with notes. Sakamoto always preferred live performances. I remember him asking: "Can we introduce more spontaneity and get the actors responding to change as it happens on stage?"

You could entrust the performing to the performers.

I think Sakamoto wanted the performers to exist as themselves in that moment on stage. Sakamoto said: "I want to create a performance with no beginning and no end. One where audiences can arrive and leave when they please."

TIME opens with the sound of Miyata's shō. During a recent discussion with Tanaka, Miyata interestingly said that the sound begins before the audience even hears it and continues after the performance has ended. More than the sound of her instrument, I think she was also referring to the sounds her body itself makes when playing or preparing to play. The performance begins before it starts and continues after it ends. I understood exactly what she meant. Indeed, where does a performance begin and end? If you watch the performance with attuned senses, you can begin to detect a kind of continuity. I hope audiences are able to share in this experience of time.

Scenes transcend time and seamlessly merge, altering the audience's own perception of space and time.

When Sakamoto first mentioned the title TIME, I began thinking about the relationship between time and space, and what it might feel like to perceive time as non-continuous. Sakamoto selected the texts—Ten Nights of Dreams, Kantan and The Butterfly Dream—all stories about dreams. I think he chose these texts because in the dream world, time is not sequential. Our dreams feel strangely seamless; stories nested within stories. But we can also feel time distort in the reality of our waking lives.

During the pandemic, I went to China to help Sakamoto set up his exhibition there and had to quarantine for three weeks. When I arrived at the hotel and walked up to the reception desk, I was surrounded by staff wearing white protective suits. When I emerged to check out three weeks later, I encountered the same exact scene again in the lobby. It felt like the time I spent in quarantine had simply evaporated. When I messaged as much to Sakamoto, he replied: "Yes, that's it! Remember that feeling!"

Discrete time is expressed here as a dream.

Sakamoto spent a lifetime making music. As music is truly the art of time, it should have a beginning and an end. As a non-musician, I can't wrap my head around how music could exist if time wasn't linear. But I think Sakamoto wanted to explore these further possibilities for sound and composition in a framework outside linear time.

TIME by Ryuichi Sakamoto + Shiro Takatani

Date: Mar 13-15, 2025

Venue: Lyric Theatre, The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts