Inside the Louvre Museum in Paris hangs a colossal painting measuring more than 3.5 metres tall and almost 2.5 metres wide. At its centre lies a woman draped in a tattered red robe, her pale, swollen body exuding the unmistakable stench of death. Around her, a group of grief-stricken peasants gather, their faces etched with sorrow and despair. The entire scene is shrouded in sombre tones, as if trapped in perpetual mourning. Only a faint beam of light slips through a window, illuminating the woman's lifeless face. Surprisingly, this is not an anonymous victim of poverty or the plague—but the Virgin Mary herself.

In 1600, the Church of Santa Maria della Scala in Rome commissioned Caravaggio to paint the Virgin. After five years of labour, he completed Death of the Virgin, only to face fierce backlash from the church, which denounced the work as blasphemous and offensive. The Virgin, a symbol of purity and divinity, was expected to appear immaculate and incorrupt. Yet Caravaggio rendered her as a mortal woman—pale, lifeless and heartbreakingly human—starkly at odds with the exalted depictions favoured by his contemporaries. Collector Giulio Mancini even accused Caravaggio of using a prostitute as a model for Mary, fuelling public outrage. Ultimately, the church refused to install the painting in the chapel.

This painting became one of the most iconic examples of why Caravaggio was viewed as a heretic in the art world. A pioneer of realism, he pioneered the chiaroscuro technique—the dramatic interplay of light and shadow—leaving an indelible mark on Baroque art. But his themes were often violent or grotesque: decapitations, dismemberment and raw human suffering were common subjects. He never depicted saints as serene or divine, but as tormented figures, revealing the frailty and deceit at the heart of human nature. He frequently used the urban poor as models, grounding sacred scenes in gritty, earthly realism.

Caravaggio lost both parents at a young age. After moving to Milan, he worked under painter Giuseppe Cesari. By day, he painted; by night, he indulged in drinking, brothels and frequent brawls. He befriended society's outcasts—gamblers, sex workers—many of whom appeared in his early works. During these tumultuous years, the married Caravaggio fell in love with a teenage Sicilian boy, Mario Minniti, immortalising his beauty in Boy with a Basket of Fruit.

In 1606, Caravaggio killed a man in a street fight—an altercation allegedly connected to Minniti. Fleeing Rome, he found refuge with the powerful Colonna family in Naples, where his artistic career flourished. In 1610, as he prepared to return to Rome, Caravaggio died mysteriously in Porto Ercole at the age of 38. The cause of death remains unknown, adding another layer of mystery to his already legendary life.

Caravaggio's life and art have inspired generations of creatives. Among them is Italian choreographer Mauro Bigonzetti. Originally trained in fine art, Bigonzetti was long immersed in the visual world before turning to dance. When the Staatsballett Berlin commissioned a work rooted in Italian culture, he immediately chose Caravaggio as his subject. He told FestMag: "The performance highlights Caravaggio's inspiration and his observations of society, of the lowest people in society. The most earthly person becomes sacred in his paintings."

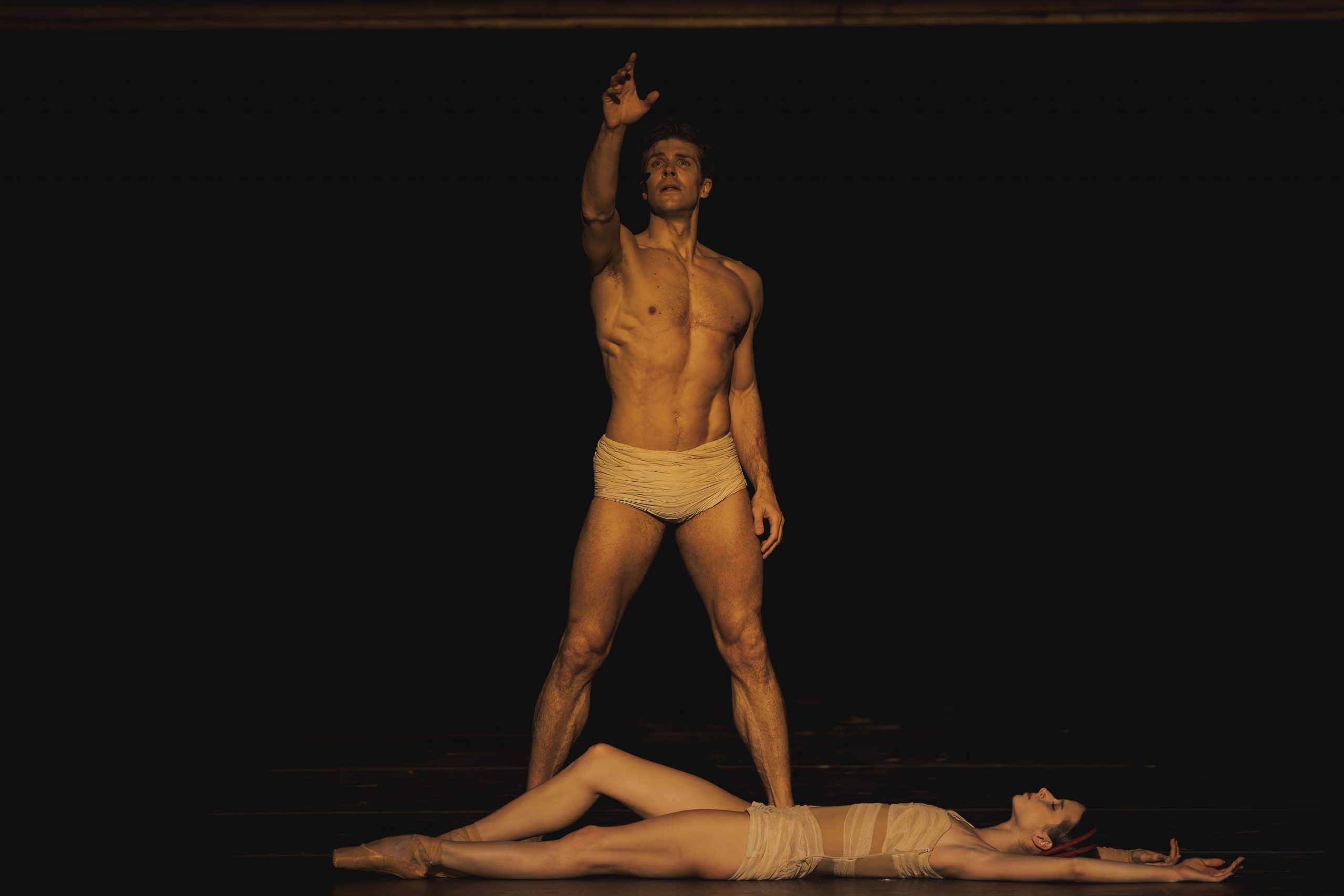

The ballet Caravaggio will make its Asia premiere at the 54th Hong Kong Arts Festival, starring celebrated dancer Roberto Bolle in a collaboration with the production company ARTEDANZASRL. "It wasn't easy to immerse myself in Caravaggio's life and personality, as he was a figure of great complexity with many darker aspects—very different from myself," Bolle tells FestMag. "However, the challenge made the experience deeply stimulating. What helped me the most was repeatedly studying his works. His genius is undeniable and, through his paintings, I was able to grasp the depth of his character and emotions."

Minimalist in stage design and cloaked in deep, moody lighting, Caravaggio visually echoes the aesthetics of the painter's work and its signature tenebrism. "The most important element is the relationship between the choreographer and lighting designer. The set design and choreography are the result of much preparation. The objective is to drown the bodies in light and shadow, imitating the chiaroscuro technique," Bigonzetti says.

Composer Bruno Moretti re-imagines Monteverdi's operatic masterpieces into a sweeping symphonic score that evokes the atmosphere of the 16th century. In the climax of Act I, a giant golden frame descends as a crimson curtain drops to the floor—symbolising the fateful murder of 1606 and mirroring the vivid blood-red strokes that so often appear in Caravaggio's paintings.

Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, in Crime and Punishment, proposed the theory of the "extraordinary man"—someone whose genius or destiny entitles him to transcend moral and legal boundaries in pursuit of a higher purpose. Caravaggio may well have been such a man: volatile, extreme, even murderous—yet history remembers him for his art. This does not excuse his crimes. But perhaps, beyond morality and law, there is another measure of a person: the depth of their talent, creativity and human insight—a capacity to bring a ray of light even into the darkest places.

Roberto Bolle—Caravaggio

Date: Mar 7–9, 2026

Venue: Grand Theatre, Hong Kong Cultural Centre

Detail: https://www.hk.artsfestival.org/en/programme/Roberto-Bolle-Caravaggio?