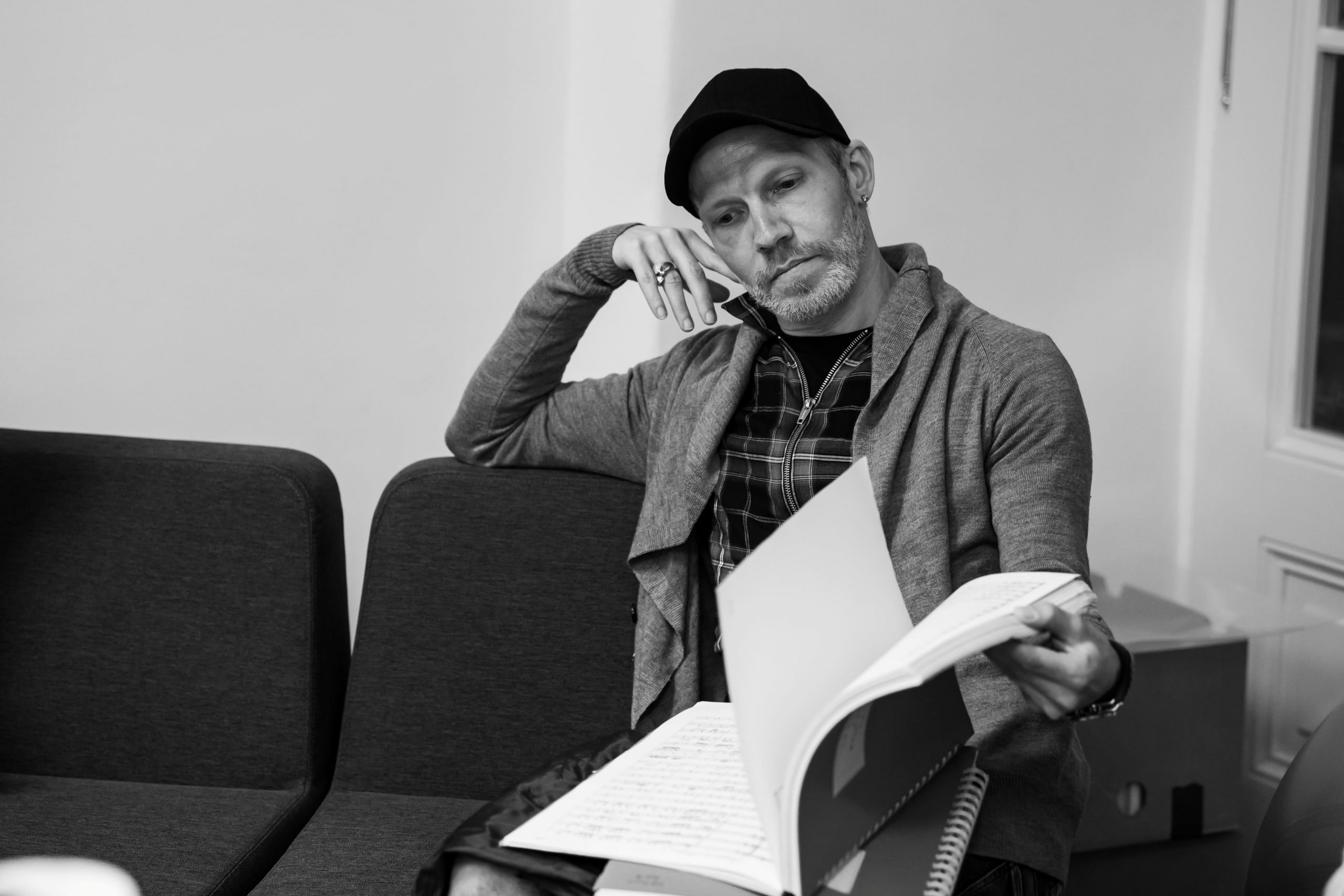

How do audiences today relate to a love story between a Scotsman and a supernatural creature that premiered in 1832? For Johan Kobborg, who is staging an historically informed La Sylphide for the Czech National Ballet, it's all about perspective. The symbolism of the supernatural can be interpreted in many ways today and the pursuit of happiness is a universal theme. While contemporary audiences may not be as steeped in Romantic fantasies as their 19th-century counterparts, Kobborg believes the era's artful storytelling remains as powerful as ever.

La Sylphide opens with a sleeping young man named James, who is awakened by a sylph, a woodland fairy from European folklore. He immediately falls in love with her, but he is due to marry his fiancé, Effy, that very day. Should he pursue a love that transcends the conventional future that awaits him? Or is he simply suffering the temporary effects of enchantment?

Revisiting a classic

Widely considered the first major Romantic ballet, La Sylphide premiered in 1832 at the Paris Opera, a version that has now been lost. At the Royal Danish Ballet, however, another version has been part of the company's repertoire since 1836. That production was created by legendary ballet master August Bournonville (1805-79), who was inspired to choreograph his own La Sylphide in Copenhagen after attending a performance in the French capital. Nearly 200 years later, Kobborg, former principal dancer with the Royal Danish Ballet and Royal Ballet in London, has painstakingly revisited the earliest-known surviving La Sylphide, reintegrating historic details while carefully considering how best to convey the ballet's story in the present.

Just before Kobborg's La Sylphide was premiered in 2005, a fortuitous discovery bestowed an additional aura on the production: a library in Sweden unearthed an orchestral score with Bournonville's handwritten notes that had never been seen in our time. Using these historic pearls of wisdom, Kobborg's version includes elements of the Danish La Sylphide that had disappeared from previous iterations of the ballet, including the placement of the characters on stage, as well as musical passages that had been eliminated over the years. Thanks to insights provided by Bournonville's notes, Kobborg confirms, "I have not cut anything from what is considered as close to the original as possible, but I have added things that used to be in the early versions of Bournonville".

The Bournonville style

Viewing a Bournonville ballet provides an interesting perspective on historic dance, allowing audiences to observe ballet steps that Kobborg asserts "have survived more or less in an unbroken chain, so they have been passed down from dancer to dancer". He remarks that Bournonville's choreography is partly the result of Danish stages that have traditionally been smaller than those in other nations. This affects the dancers' physical movements and spatial patterns because "the larger the stage, the larger your movements", Kobborg says.

The Bournonville style also emphasises an understated approach to placement. The arms, for example, function as an organic continuation of the entire body without emphasis. Kobborg says: "In Bournonville, we try not to show any effort, the arms are not placed for affect." The style also includes the use of mime, an integral element of the ballet master's storytelling. The Danish choreographer believed that dancing was an expression of joy, therefore "in Bournonville, people dance when they're happy", says Kobborg, while the rest of the storytelling occurs through mime. These subtle differences can be a challenge for dancers unfamiliar with Bournonville's style, but Kobborg recalls that the Czech dancers in La Sylphide were able to adapt quickly due to the diverse repertoire of their Prague-based company, in contrast to performers accustomed to a single choreographer or stylistic tradition.

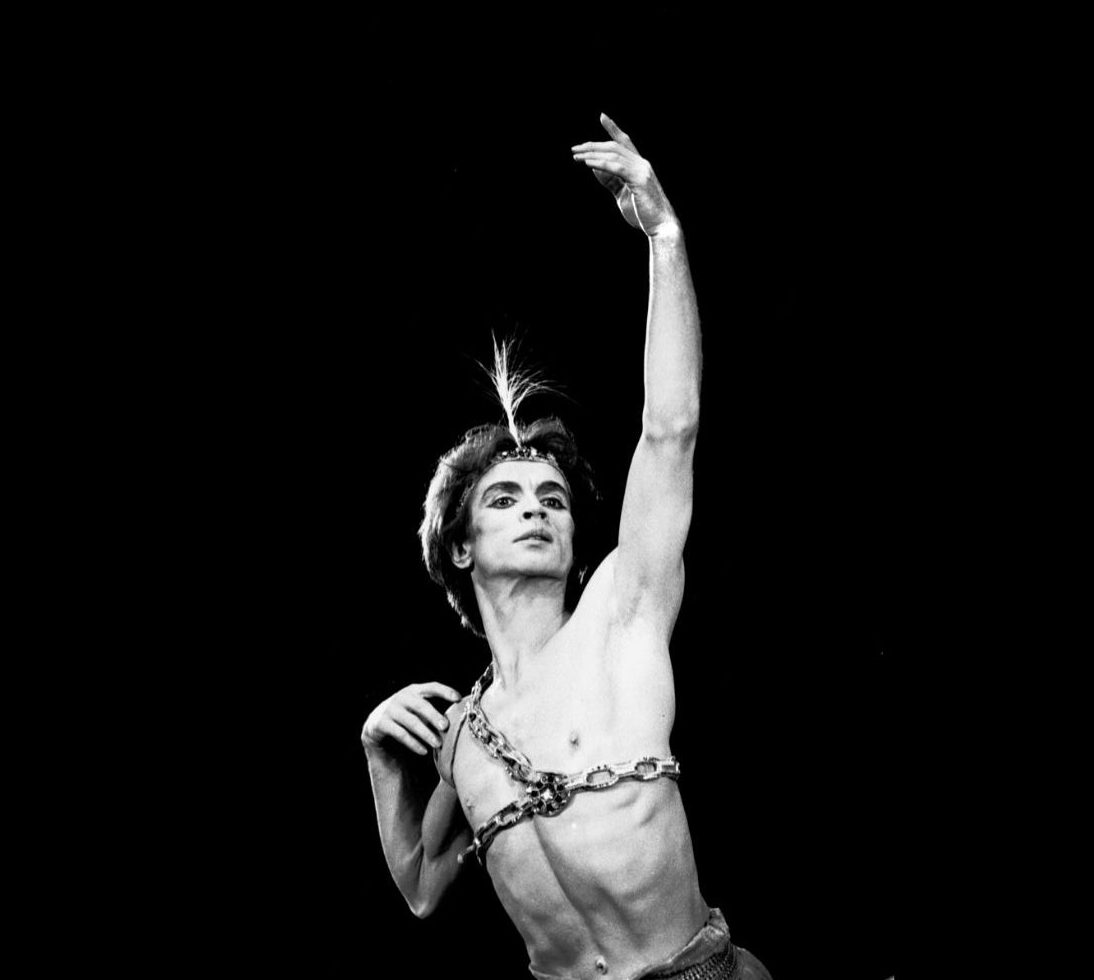

The male dancer and Bournonville

As a respected dancer himself, Bournonville did much to promote the position of the male dancer. Kobborg describes how Bournonville reimagined partnering in which the male was no longer hidden behind the female for support. Instead, the two danced side by side, executing the same steps at the same time, something Kobborg considers "uniquely Bournonville". One of the reasons that many men consider it so fulfilling to perform in Bournonville ballets is "because you are as important as your female counterpart". Kobborg considers James, the male protagonist of La Sylphide, to be one of the most demanding and exciting roles in the Bournonville repertoire, saying it's a part "that you don't get tired of performing, as with the best ballets, you can evolve your interpretation because there is room for growth".

In addition to the ballets themselves, Bournonville training is particularly well suited to preparing strong male dancers. In contrast to other styles, men trained in Bournonville don't use their arms to propel themselves through space while performing large leaps, nor are they taught to show any effort, but "we are expected to jump just as high", says Kobborg. That strength, he concludes, "must be found somewhere else, in your legs and in your upper body", creating a solid foundation that builds strength and ease.

Today, both men and women can benefit from Bournonville's training while offering their own unique contributions to his 19th-century choreography through their own interpretations and small adjustments that combine the best of old- and new-world approaches.

The Scottish kilt

James' tartan kilt immediately identifies the ballet's setting as Scotland, an exotic locale in keeping with Romanticism's focus on untamed environments. While tights normally display the entire line of the male dancer's legs, the kilt covers the thighs, framing the quick and precise choreography for the lower legs and feet.

A world of fairytales

Lifelong friends since childhood, August Bournonville and Hans Christian Andersen shared a love of dance. While Andersen did not perform professionally like his schoolmate, he wrote influential fairytales that blurred the line between reality and fantasy, contributing to ballet's world of magical spirits such as those that populate La Sylphide.

Pointe shoes fit for a sylph

To enhance her role in the original production in 1832 of La Sylphide, ballerina Marie Taglioni wore a pair of pointe shoes, underscoring the sylph's supernatural grace and weightlessness. Pointe shoes had originally been used by acrobats as a balancing trick, but Taglioni transformed them into an enduring symbol of ballet's artistry.

The male dancer and Bournonville

As a respected dancer himself, Bournonville did much to promote the position of the male dancer. Kobborg describes how Bournonville reimagined partnering in which the male was no longer hidden behind the female for support. Instead, the two danced side by side, executing the same steps at the same time, something Kobborg considers "uniquely Bournonville". One of the reasons that many men consider it so fulfilling to perform in Bournonville ballets is "because you are as important as your female counterpart". Kobborg considers James, the male protagonist of La Sylphide, to be one of the most demanding and exciting roles in the Bournonville repertoire, saying it's a part "that you don't get tired of performing, as with the best ballets, you can evolve your interpretation because there is room for growth".

In addition to the ballets themselves, Bournonville training is particularly well suited to preparing strong male dancers. In contrast to other styles, men trained in Bournonville don't use their arms to propel themselves through space while performing large leaps, nor are they taught to show any effort, but "we are expected to jump just as high", says Kobborg. That strength, he concludes, "must be found somewhere else, in your legs and in your upper body", creating a solid foundation that builds strength and ease.

Today, both men and women can benefit from Bournonville's training while offering their own unique contributions to his 19th-century choreography through their own interpretations and small adjustments that combine the best of old- and new-world approaches.

The Czech National Ballet—La Sylphide

Date: 6-8 Mar 2025

Venue: Grand Theatre, Hong Kong Cultural Centre