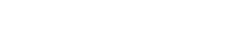

While a student at the Central Academy of Drama in Beijing in 1991, Meng Jinghui chose Samuel Beckett's absurdist play Waiting for Godot as his graduation piece—an unconventional choice in an era still dominated by realist drama. "At the time, it was as though I was waiting for a new world, waiting for something different to happen in that new world ... It was a youthful impulse, coupled with an ambition to subvert existing aesthetics."

The most subversive thing about this rendition was perhaps the bold manner in which he tampered with the original plot. In Beckett's play, "Godot", the titular character the two protagonists are waiting for, never shows up. But in Meng's 1991 version, he does arrive, only to be strangled silently. Why kill Godot? "I think in facing this absurd world, we must find the courage to transcend it. The death of Godot means that one can wait in perpetuity and live forever in a state of defiance and anger."

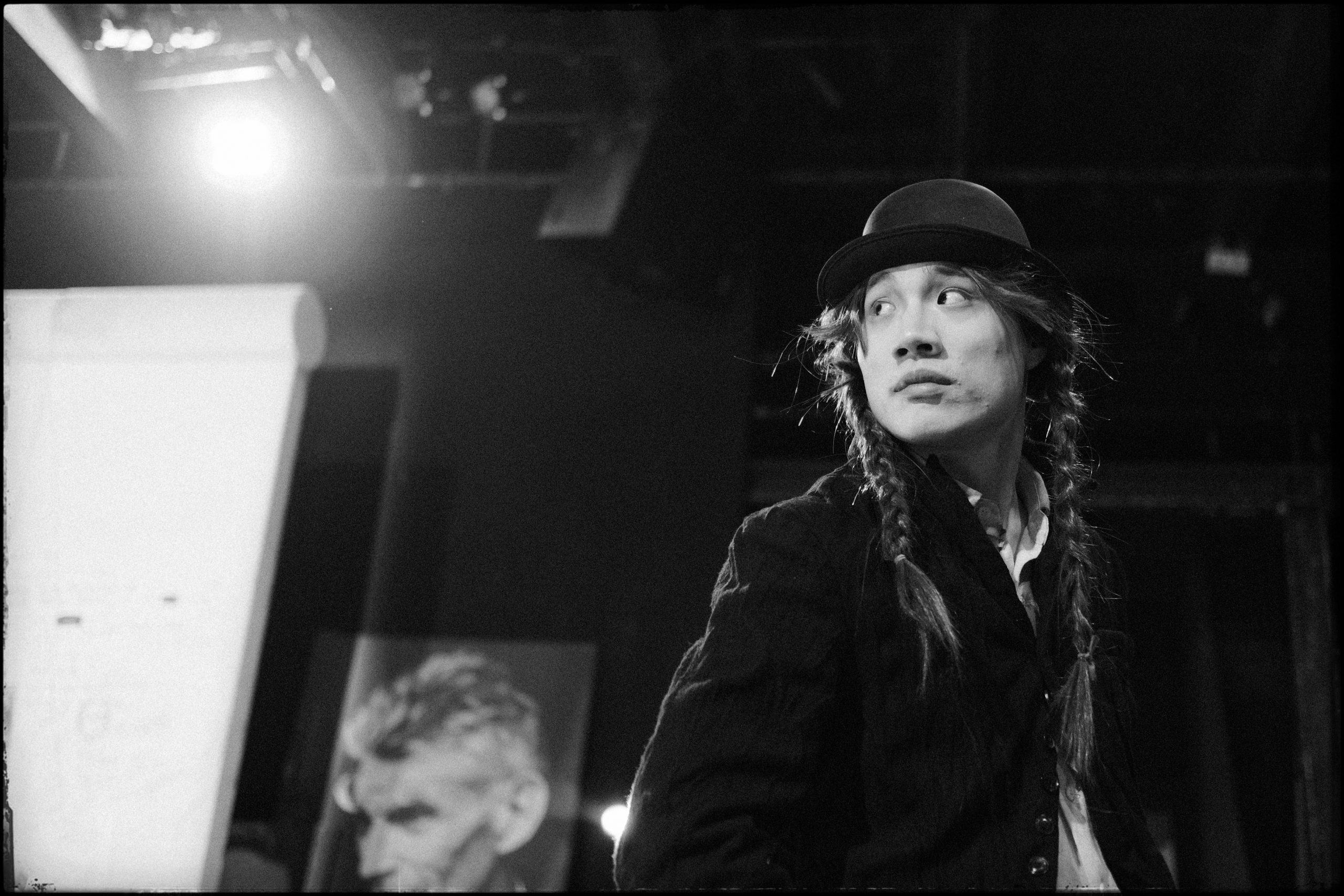

Thirty-three years on, Meng has decided to stage Waiting for Godot again and will bring this latest version to the HKAF this March. The world, it seems, is still absurdly in need of Beckett—and Meng, with his signature playfulness and a sensitivity unique to his milieu, emerges as the ideal spokesperson for the playwright in the 21st century. His fixation with breaking new ground has also led to him taking the concept of "waiting" to new heights. While Godot does not appear in this re-staging, a pair of mysterious guests do—which essentially turn the act of waiting into eternity.

If the 1991 version embodied the "waiting" that Meng's generation went through as they grew up in the '70s and '80s, perhaps the 2024 rendition is about the absence of "waiting" in the 21st century. "In the old days, whether waiting at a hospital or for a flight, people would sit tight and observe what was happening around them as they waited. But now, the act of waiting is rare—people have been given a virtual world and their imaginations have become as thin as their phones." In this re-staging, the audience is kept busy even before the performance begins: they can step onto the stage and scribble on the walls at will, and those same panels will be used again for the next performance, allowing thoughts and memories to pass on in a palimpsestic manner. Is this not a form of transcendence?

Speaking of another of his major revivals, I Love XXX (1994), Meng Jinghui quipped: "You might wonder—why are we still willing to perform this play after 30 years? Some things I hope transcend time." Waiting may no longer be an issue in contemporary times, but Meng, through his work, opens up a channel where people from various times can connect and share their differences. What happens then, 30 years from now? Surely we will find out—hopefully when Meng's next Godot comes out.

MENG Theatre Studio—En attendant Godot (Waiting for Godot)

Date: 12-15, Mar 2026

Venue: Theatre, Hong Kong City Hall

Details: https://www.hk.artsfestival.org/en/programme/Waiting-for-Godot