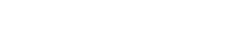

"The Painted Skin", a story from the classic story collection Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio by Qing dynasty writer Pu Songling, has regularly been adapted for film and television series, but rarely as a Cantonese opera. This alone makes the original Cantonese opera based on the story written by Tse Hue-ying, a local performer and playwright, unique enough, but she has gone even further. In her opera version of The Painted Skin, Tse takes on two main roles: the fox spirit who turns into a young woman and seduces a married man named Wang, and his faithful yet indifferent wife, Chen. The acting challenge facing Tse is significant, given that the two characters are going to different extremes.

A multi-faceted Cantonese opera

The opera made its premiere in 2020 and is making a return to the 51st Hong Kong Arts Festival in 2023. With its script updated, this"refined edition" incorporates modern stage effects into a traditional Cantonese opera, which is simply the icing on the cake.

Returning with The Painted Skin after almost four years, Tse emphasises in an interview with FestMag that the plot is now more tightly knit and cinematic, while preserving the stylised movements and postures of Cantonese opera tradition. In the prologue, for example, when the dancers playing fox spirits put on masks representing human faces, the stage lighting is dimmed, making the emergence of the fox spirits uncanny and hallucinatory, highlighting the message of the story: that appearances can be deceptive.

Despite adopting forms of expression from modern theatre, the opera performance fuses together influences from various schools of traditional Chinese opera. The co-directors are a renowned Yue opera performer from Shanghai, Shi Jihua, and Wang Lei, a Peking opera performer and the daughter of notable Kun opera artist Wang Zhiquan. Tse became a student of Shi and Wang in 2014, so The Painted Skin subtly takes inspiration from Yue opera, Kun opera and Peking opera.

While revising the script with Tse, Master Shi reinforced the importance of maintaining the taste of Cantonese opera. Tse says: "The performance style of Shanghai Yue opera is very much resembles everyday life, rendering every detail of the gestures and facial expressions." To construct the characters of the two contrasting female protagonists, Mei and Chen, Tse frequently sought guidance from Wang. Though Wang was in mainland China, she gave advice on the characters' postures when sitting and standing, their facial expressions and vocal tones. For example, Mei usually tilts her head, glancing at Wang, while Chen is always sitting upright, looking straight ahead. These details help the audience differentiate between the two characters, despite them being played by the same performer. Elements of Peking opera also enrich the diversity of emotional expressions, such as how Tse employs the"sleeve movement" from the Cheng school of Peking opera in expressing the hysteric anxiety of the normally serious Chen when learning her husband had lost his heart. These stylised movements from Peking and Kun opera are combined with the music of Cantonese opera.

Meanwhile, Tse's husband, Ko Yun-hung, serves as artistic director, music designer and music lead. He arranged repeated playing of The Scenes of Qinhuai, taken from a Jiangsu folk ditty, to arouse emotions among audience members. The piece is played when Mei enters and seduces Wang, and again when Chen is harassed by the wild monk as she attempts to save her husband. Ko says this repetition hints at the cycle of karma initiated by Wang, which unfortunately is inflicted on his wife.

Tse mentioned during a previous interview that her intention when writing original Cantonese opera scripts was to create characters for herself, which may be surprising considering how different she is from Mei and Chen. She remembers that her husband was originally not in favour of her taking on such characters, with Ko saying: "It's easy to impress the audience with these types of seductive and flirtatious characters. But once they are easily impressed, you may become stereotyped." This may be a concern for young actors, but now that Tse has gained experience playing a diverse range of characters, such as Mu Guiying, the female general, and Der Ling, the lady in waiting of Empress Dowager Cixi, this is no longer a concern.

Both Tse and Ko agree that to attract new audience members, it is important that new original Cantonese opera works are created. Although "The Painted Skin" has been widely adapted, the original text is quite short, just more than 1,000 characters long, and still contains great potential for further creative writing. Tse mentions the adaptation of Floral Princess in 1957 as an example. She says: "The performance aspects of Cantonese opera are a form of heritage passed down to us by our predecessors. We need creative works as well, but they should not be shoddily produced." And Ko, who comes from a family engaged in Cantonese opera for three generations, agrees: "Advice from experienced masters is crucial."

Cantonese Opera—The Painted Skin (Refined Edition)

Detail: https://www.hk.artsfestival.org/en/programme/the_painted_skin